谈“笑”:论古今中外各个时期的笑

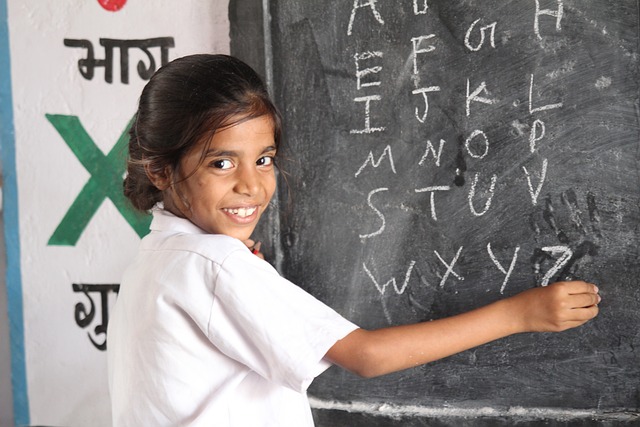

“笑”是人类最基本的情感表达方式,但中外各个历史时期对“笑”的刻画却大不相同:古希腊雕像笑得端庄高雅,佛兰芒画家笔下的少年笑得天真调皮;几百年前,人们以笑不露齿为礼仪,而今人们则开怀大笑,尽情展露内心的喜悦。

If you say cheese, you are ready for the photographer to render a picture-perfect portrait complete with smile. That’s the way it has been since around 1920, when photographers at British public schools[1] developed the tradition. And yet that is not the way it has always been.

In Australia there is a fashion for saying “money.” Spaniards say “patata” (potato) and the Japanese use the English word “whisky.” The Czechs used to use the Czech word for cheese, but now say “fax” which may hurtle them into modernity.[2] Plenty of languages don’t have a smile word; the photographers just ask for a smile and the subjects do the best they can.

We don’t smile just for the photographer, of course. Let’s examine smiles in art. You can bet the Mona Lisa is here, as is Frans Hals’s[3] Laughing Cavalier. There is a famous “archaic smile”[4] on early Greek sculpture. The figures of young men and women stand stiffly, but their mysterious smiles give them a reassuring amount of life.[5]

Dutch and Flemish painters of the 17th century had a favorite subject of the “hennetaster,” or “chicken groper,” a boy who smiles as he feels up a hen to see if she has an egg on the way.[6] These enormously popular paintings were riotously funny to their owners and the guests to whom they were displayed; the humor in part derived from the interchangeability of the Dutch words for bird, birds, or hens with those for genitalia, women, and other double entendres.[7]

Jesus smiles as he undergoes crucifixion, and some of the Romanesque sculptures,[8] which otherwise have very small mouths, are brightened by surprising smiles.

The nerves that make a natural smile are different from the ones activated when we force a smile, and so the two smiles look different; sometimes neurological patients[9] will be able to do one of the smiles but not the other. 30% of Americans show their canine teeth[10] when they smile, and only 67% turn up the corners of the mouth when they smile. No one really knows why tiny babies smile except that it is a trick calculated[11] to make the adults around them like them; of course it works.

Laughing has been thought to be bad taste; Lord Chesterfield advised his son, “The vulgar often laugh, but never smile; whereas well-bred people often smile, but seldom laugh.”[12] We are smiling more heartily now, and this is because of modern dentistry, which encourages display of healthy teeth, and modern photography, which can catch a spontaneous smile when previously sitters had to keep immobile for long periods of time to make a portrait.[13]

Vocabulary

1. public school: 在英国和威尔士指公学,一种贵族化的私立付费学校,实行寄宿制,常为大学的预科学校。在美国和苏格兰指初等或中等公立学校。

2. Czech: 捷克人(的),捷克语(的);hurtle: 猛投,猛扔;modernity: 现代状态。此处语带调侃:与欧洲发达国家相比,捷克的经济比较落后,句中作者调侃捷克人用fax(传真)一词,希望能让自己显得先进些。

3. Frans Hals: 弗兰斯•哈尔斯(1580?—1666),荷兰肖像画家和风俗画家,用色简朴而明亮,善于表现人物的个性和神态,句中提到的Laughing Cavalier(《微笑骑兵》)为其代表作。

4. archaic smile: 古风式微笑,是古希腊古风时期(the Archaic Period of Ancient Greece,约600BC—480BC)希腊雕像特有的微笑,特征为嘴角微微上扬。其研究者有两种看法:一种认为古风式微笑反映了人们健康的情绪和幸福的生活,另一种认为是雕刻难度造成的。但后人都把这种微笑视作端庄、典雅的笑容。

5. stiffly: 僵直地;reassuring: 安慰性的,使人安心的。

6. 17世纪的荷兰和佛兰芒画家喜欢将hennetaster,即“摸鸡者”作为主题,画的是一个男孩儿,一边笑一边摸着一只母鸡,看看它是不是快下蛋了。Flemish: 佛兰芒的,此处的Flemish painters指15至17世纪比利时和法国北部的佛兰芒画派的画家。

7. riotously: 非常滑稽有趣地;interchangeability: 可互换性;genitalia: 生殖器;double entendres:

(常有猥亵含义的)双关语。

8. undergo: 遭受,忍受;crucifixion: 钉死于十字架;Romanesque:(雕刻、绘画等)罗马式的,11至12世纪盛行于西欧。

9. neurological patient: 神经系统疾病患者。

10. canine tooth: 犬齿。

11. calculate: 打算,计划。

12. Lord Chesterfield: 切斯特菲尔德勋爵(1694—1773),英国著名政治家兼文人,他向儿子传授礼仪与学识的信是西方倍受推崇的家书;the vulgar: 粗俗之人,平民;well-bred people: 知书达理之人。

13. dentistry: 牙科医术;spontaneous: 自发的,(举止等)自然的;immobile: 一动不动的。

“笑”是人类最基本的情感表达方式,但中外各个历史时期对“笑”的刻画却大不相同:古希腊雕像笑得端庄高雅,佛兰芒画家笔下的少年笑得天真调皮;几百年前,人们以笑不露齿为礼仪,而今人们则开怀大笑,尽情展露内心的喜悦。

If you say cheese, you are ready for the photographer to render a picture-perfect portrait complete with smile. That’s the way it has been since around 1920, when photographers at British public schools[1] developed the tradition. And yet that is not the way it has always been.

In Australia there is a fashion for saying “money.” Spaniards say “patata” (potato) and the Japanese use the English word “whisky.” The Czechs used to use the Czech word for cheese, but now say “fax” which may hurtle them into modernity.[2] Plenty of languages don’t have a smile word; the photographers just ask for a smile and the subjects do the best they can.

We don’t smile just for the photographer, of course. Let’s examine smiles in art. You can bet the Mona Lisa is here, as is Frans Hals’s[3] Laughing Cavalier. There is a famous “archaic smile”[4] on early Greek sculpture. The figures of young men and women stand stiffly, but their mysterious smiles give them a reassuring amount of life.[5]

Dutch and Flemish painters of the 17th century had a favorite subject of the “hennetaster,” or “chicken groper,” a boy who smiles as he feels up a hen to see if she has an egg on the way.[6] These enormously popular paintings were riotously funny to their owners and the guests to whom they were displayed; the humor in part derived from the interchangeability of the Dutch words for bird, birds, or hens with those for genitalia, women, and other double entendres.[7]

Jesus smiles as he undergoes crucifixion, and some of the Romanesque sculptures,[8] which otherwise have very small mouths, are brightened by surprising smiles.

The nerves that make a natural smile are different from the ones activated when we force a smile, and so the two smiles look different; sometimes neurological patients[9] will be able to do one of the smiles but not the other. 30% of Americans show their canine teeth[10] when they smile, and only 67% turn up the corners of the mouth when they smile. No one really knows why tiny babies smile except that it is a trick calculated[11] to make the adults around them like them; of course it works.

Laughing has been thought to be bad taste; Lord Chesterfield advised his son, “The vulgar often laugh, but never smile; whereas well-bred people often smile, but seldom laugh.”[12] We are smiling more heartily now, and this is because of modern dentistry, which encourages display of healthy teeth, and modern photography, which can catch a spontaneous smile when previously sitters had to keep immobile for long periods of time to make a portrait.[13]

Vocabulary

1. public school: 在英国和威尔士指公学,一种贵族化的私立付费学校,实行寄宿制,常为大学的预科学校。在美国和苏格兰指初等或中等公立学校。

2. Czech: 捷克人(的),捷克语(的);hurtle: 猛投,猛扔;modernity: 现代状态。此处语带调侃:与欧洲发达国家相比,捷克的经济比较落后,句中作者调侃捷克人用fax(传真)一词,希望能让自己显得先进些。

3. Frans Hals: 弗兰斯•哈尔斯(1580?—1666),荷兰肖像画家和风俗画家,用色简朴而明亮,善于表现人物的个性和神态,句中提到的Laughing Cavalier(《微笑骑兵》)为其代表作。

4. archaic smile: 古风式微笑,是古希腊古风时期(the Archaic Period of Ancient Greece,约600BC—480BC)希腊雕像特有的微笑,特征为嘴角微微上扬。其研究者有两种看法:一种认为古风式微笑反映了人们健康的情绪和幸福的生活,另一种认为是雕刻难度造成的。但后人都把这种微笑视作端庄、典雅的笑容。

5. stiffly: 僵直地;reassuring: 安慰性的,使人安心的。

6. 17世纪的荷兰和佛兰芒画家喜欢将hennetaster,即“摸鸡者”作为主题,画的是一个男孩儿,一边笑一边摸着一只母鸡,看看它是不是快下蛋了。Flemish: 佛兰芒的,此处的Flemish painters指15至17世纪比利时和法国北部的佛兰芒画派的画家。

7. riotously: 非常滑稽有趣地;interchangeability: 可互换性;genitalia: 生殖器;double entendres: <法>(常有猥亵含义的)双关语。

8. undergo: 遭受,忍受;crucifixion: 钉死于十字架;Romanesque:(雕刻、绘画等)罗马式的,11至12世纪盛行于西欧。

9. neurological patient: 神经系统疾病患者。

10. canine tooth: 犬齿。

11. calculate: 打算,计划。

12. Lord Chesterfield: 切斯特菲尔德勋爵(1694—1773),英国著名政治家兼文人,他向儿子传授礼仪与学识的信是西方倍受推崇的家书;the vulgar: 粗俗之人,平民;well-bred people: 知书达理之人。

13. dentistry: 牙科医术;spontaneous: 自发的,(举止等)自然的;immobile: 一动不动的。