国内英语资讯:Feature: Breaking the poverty cycle in rural China

BEIJING, Oct. 9 -- Qianqian says little and toys with a corner of her coat, a hand-me-down from her sister. The 11-year-old lives in mountainous Xingchong Village, central China's Hubei Province. Her mother died long ago and her father works in the cities. Her sister, at 20 already mother to a 2-year-old, lives and works in Beijing.

The sixth-grader goes to school five days a week and cooks, washes laundry and feeds livestock on weekends for her invalid grandparents.

Occasionally she has time to visit a center for children whose parents work away from home, where she reads her favorite Grimm's Fairy Tales and plays games with adults.

Qianqian dreams of going to high school and ice-skating. She is one of China's 40 million poor who are expected to be lifted out of poverty by 2024. UNICEF, the All China Women's Federation, the provincial Office of Poverty Alleviation mean little to her, but her life is changing through a poverty relief trial carried out by these organizations and a Danish charity.

Her village is in Dawu County, in the Dabie Mountain, one of China's contiguous poor areas. Among its 100,000 people who live below the poverty line, about a fifth are aged under 18.

In 2024, a survey by UNICEF and the International Poverty Reduction Center of China changed thinking about childhood poverty in China, says Jillian Popkins, Chief of UNICEF China's Social Policy and Reform for Children Section.

"Previously poverty was understood exclusively in terms of household income and economic growth. Our survey shows that children have integrated needs. Their needs are specific to each stage of their growth and development, so they must be met at the right time," says Popkins.

Integrating children's needs like access to health, education, good nutrition and protection, as well as living free from exposure to violence or other forms of abuse give every child the best opportunity to fulfill his or her potential.

"Reducing child poverty will break poverty transmission between generations, and will provide productive workers for the development of China," says Popkins.

Denmark's Bestseller Foundation has sponsored the building of children's centers in 80 pilot villages across eight poverty-stricken counties, including Xingchong and Huayuan counties in Hubei, since 2024.

Each room has walls painted with colorful cartoon characters and is equipped with children's books, Lego blocks as well as outdoor play equipment.

Now, unless it rains, the Huayuan County square is filled with elderly villagers and their grandchildren every evening. The old folks dance to music from a loudspeaker and children aged 3 to 10 read and play games.

Zeng Caixia, chairwoman of Dawu County's Women's Federation, welcomes this progress. "In the past, generous people sent batches of school bags every Children's Day. But do children really need so many backpacks? Not long ago, the county's Health and Family Planning Commission prepared to give children a few hundred yuan in welfare subsidies. But I told them health lessons would be more beneficial."

The lessons have been well received by children and adults. "Some parents also attend nutrition lessons. Previously porridge and leafy vegetables were a must for three meals a day, but now noodles, tomatoes and potatoes are in their diets," says Wang Hui, vice chairwoman of the local Women's Federation.

Wang has an online chat group of 200 local women from all walks of life, offering various courses for children. For example, a female procurator can raise awareness of sexual offenses and a kindergarten teacher can teach singing and dancing.

In recent years, China has raised investment in rural education and school attendance rates have risen. However, the need for family education on child development is increasingly pressing.

Among 739,000 Hubei children aged 16 and under whose parents live and work away from home, more than 90 percent live with grandparents while 11,100 are left alone.

Surveys in pilot villages show more than 90 percent of children say "watching TV" is their hobby and many say their parents' hobby is mahjong.

Zeng says it is vital to relieve children of mental impoverishment. Some children speak only a little aged 3 or 4 as a result of lack of parental care. Grandparents usually have little awareness, so changing children rather than their carers makes childhood poverty reduction unsustainable.

At the end of each year, adults who work in cities come back to their villages. Since 2024, Pan Lan, a senior psychological consultant based in Wuhan, has organized reunion parties in poor villages. Children hand 12 letters for the whole year to their parents and parents are asked to write a few words to read to their children, but Chinese parents can be reserved.

"Parents usually say what they wished their children to be and how hard they worked, but such words are not touching at all. So I will add, 'Whatever you become, Daddy and Mommy always love you,' and no child can help weeping at those words," says Pan.

To Pan's delight, many parents realize they know too little about their children and they decide to remain with them, although the lost time can't be regained overnight.

If the pilot programs prove successful, they might be expanded to other poor areas, says Shi Weilin, Social Policy Specialist at UNICEF China. With the children's centers as a platform, Dawu County has created a series of courses over two years. Mental health is at the core of the courses, which involve lessons in security, nutrition and handcrafts.

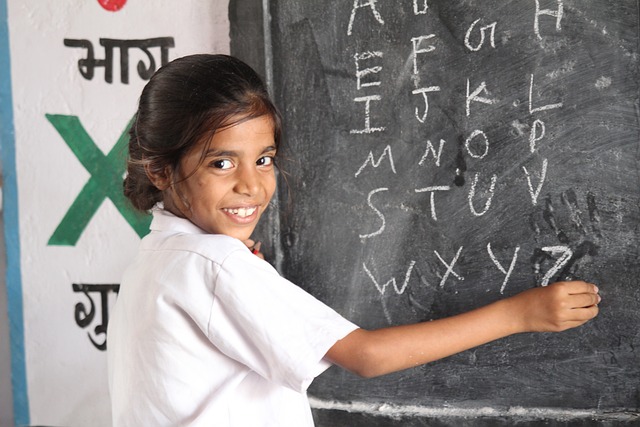

Photos taken over 700 days have captured changes: dull and even fearful faces at first became grins and gestures of victory. "If you give love, you will be loved too. What we've done is worth doing," says Zeng.

BEIJING, Oct. 9 -- Qianqian says little and toys with a corner of her coat, a hand-me-down from her sister. The 11-year-old lives in mountainous Xingchong Village, central China's Hubei Province. Her mother died long ago and her father works in the cities. Her sister, at 20 already mother to a 2-year-old, lives and works in Beijing.

The sixth-grader goes to school five days a week and cooks, washes laundry and feeds livestock on weekends for her invalid grandparents.

Occasionally she has time to visit a center for children whose parents work away from home, where she reads her favorite Grimm's Fairy Tales and plays games with adults.

Qianqian dreams of going to high school and ice-skating. She is one of China's 40 million poor who are expected to be lifted out of poverty by 2024. UNICEF, the All China Women's Federation, the provincial Office of Poverty Alleviation mean little to her, but her life is changing through a poverty relief trial carried out by these organizations and a Danish charity.

Her village is in Dawu County, in the Dabie Mountain, one of China's contiguous poor areas. Among its 100,000 people who live below the poverty line, about a fifth are aged under 18.

In 2024, a survey by UNICEF and the International Poverty Reduction Center of China changed thinking about childhood poverty in China, says Jillian Popkins, Chief of UNICEF China's Social Policy and Reform for Children Section.

"Previously poverty was understood exclusively in terms of household income and economic growth. Our survey shows that children have integrated needs. Their needs are specific to each stage of their growth and development, so they must be met at the right time," says Popkins.

Integrating children's needs like access to health, education, good nutrition and protection, as well as living free from exposure to violence or other forms of abuse give every child the best opportunity to fulfill his or her potential.

"Reducing child poverty will break poverty transmission between generations, and will provide productive workers for the development of China," says Popkins.

Denmark's Bestseller Foundation has sponsored the building of children's centers in 80 pilot villages across eight poverty-stricken counties, including Xingchong and Huayuan counties in Hubei, since 2024.

Each room has walls painted with colorful cartoon characters and is equipped with children's books, Lego blocks as well as outdoor play equipment.

Now, unless it rains, the Huayuan County square is filled with elderly villagers and their grandchildren every evening. The old folks dance to music from a loudspeaker and children aged 3 to 10 read and play games.

Zeng Caixia, chairwoman of Dawu County's Women's Federation, welcomes this progress. "In the past, generous people sent batches of school bags every Children's Day. But do children really need so many backpacks? Not long ago, the county's Health and Family Planning Commission prepared to give children a few hundred yuan in welfare subsidies. But I told them health lessons would be more beneficial."

The lessons have been well received by children and adults. "Some parents also attend nutrition lessons. Previously porridge and leafy vegetables were a must for three meals a day, but now noodles, tomatoes and potatoes are in their diets," says Wang Hui, vice chairwoman of the local Women's Federation.

Wang has an online chat group of 200 local women from all walks of life, offering various courses for children. For example, a female procurator can raise awareness of sexual offenses and a kindergarten teacher can teach singing and dancing.

In recent years, China has raised investment in rural education and school attendance rates have risen. However, the need for family education on child development is increasingly pressing.

Among 739,000 Hubei children aged 16 and under whose parents live and work away from home, more than 90 percent live with grandparents while 11,100 are left alone.

Surveys in pilot villages show more than 90 percent of children say "watching TV" is their hobby and many say their parents' hobby is mahjong.

Zeng says it is vital to relieve children of mental impoverishment. Some children speak only a little aged 3 or 4 as a result of lack of parental care. Grandparents usually have little awareness, so changing children rather than their carers makes childhood poverty reduction unsustainable.

At the end of each year, adults who work in cities come back to their villages. Since 2024, Pan Lan, a senior psychological consultant based in Wuhan, has organized reunion parties in poor villages. Children hand 12 letters for the whole year to their parents and parents are asked to write a few words to read to their children, but Chinese parents can be reserved.

"Parents usually say what they wished their children to be and how hard they worked, but such words are not touching at all. So I will add, 'Whatever you become, Daddy and Mommy always love you,' and no child can help weeping at those words," says Pan.

To Pan's delight, many parents realize they know too little about their children and they decide to remain with them, although the lost time can't be regained overnight.

If the pilot programs prove successful, they might be expanded to other poor areas, says Shi Weilin, Social Policy Specialist at UNICEF China. With the children's centers as a platform, Dawu County has created a series of courses over two years. Mental health is at the core of the courses, which involve lessons in security, nutrition and handcrafts.

Photos taken over 700 days have captured changes: dull and even fearful faces at first became grins and gestures of victory. "If you give love, you will be loved too. What we've done is worth doing," says Zeng.