The gold-digging game

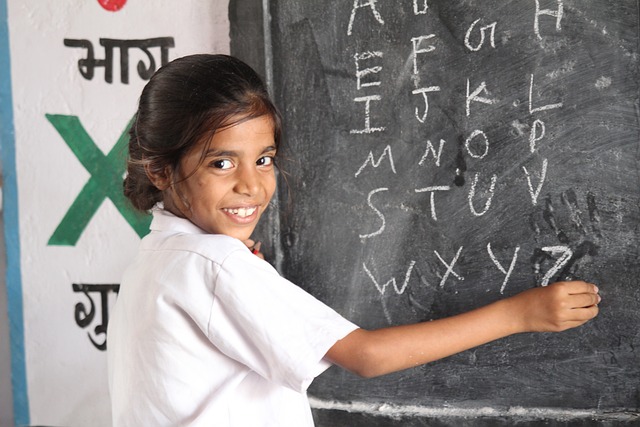

If You Are the One shot to notoriety when it highlighted gold diggers like

Ma Nuo. Provided to China Daily

China's first successful dating show is under attack for showcasing materialistic starlets and wannabes rather than true love.

When Jiangsu Satellite Television came out with a hit show early this year my sixth sense told me it would be axed.

If You Are the One is not China's first dating show, but it is the country's first successful one. For each episode, 24 young women stand behind a podium, in control of a light. Half a dozen bachelors are paraded, one for each 10-minute segment. The female contestants turn off the light when they decide to opt out. After several rounds of "showing off his talent", including expositions on love and marriage, the guy gets to choose one of the women who still have their lights on.

The bachelor either walks away with one of the women or, more likely, leaves alone. After which another bachelor is brought in.

What makes the show spicy is the remarks by the female participants when they comment on the bachelor. As there are 24 of them and not everyone is given equal opportunity to pontificate, they have a tendency to make utterances that will not fall to the cutting floor during editing.

One of the women described her marital vision as such: "I'd rather be miserable sitting in a BMW than be happy riding a bicycle." As the bicycle is a mode of transport in China, not a tool of recreation or fitness, what Ma Nuo, a budding model, wants is very clear: wealth over love. She knows money may not bring her happiness, but it is her top priority nonetheless.

This statement quickly became the de facto motto for women like her, and by extension, this dating show, which borrows its title from an earlier hit feature film. For a while, there were so many material girls and gold diggers on China's small screens you'd be forgiven for thinking it was 1920s New York.

Essentially, the show is a victim of its own success. Before the industry watchdogs unleashed their fury, even usually liberal commentators were condemning it as "too boorish". However, defenders had a point when they said the show accurately reflected our social mentality. Say what you like, this is how a lot of Chinese approach dating and mating.

We Chinese, especially women, have always attached great importance to the social status of those we want to marry. Today status is mostly embodied in bank accounts, outsized housing units and luxury vehicles. In the more "idealistic" time when I was a kid, people looked at things like social class - whether one's family was "revolutionary" enough. The very first question asked about a potential date often was: What does his father do?

A 22-year-old might not have much, but if his daddy was a cadre his road ahead was paved with roses. Dating was an elaborate ritual then. Young men and women would turn to a matchmaker, usually a middle-aged woman, for help. She would search her mental database and call up like-minded middle-aged women. When a candidate was identified, she would arrange a meeting for the two. It often took place in a park or at a cinema. The cost involved was not much more than a movie ticket or some snack.

Both sides would report to the "auntie". If one party said "yes" and the other "no", the one who said no would be grilled: "What don't you like about her? I don't see anything wrong? You two look perfect together."

If you turned down two or three dates, you would risk being an outcast. The matchmaker would label you as "too picky" and delete you from her database. And if she happened to be your colleague, you might be bumped from your next promotion.

Chinese are extremely status-conscious when it comes to dating and marriage.

It only happens in fairy tales that a poor boy meets a rich girl and they

get to live happily ever after. Wang Xizeng / For China Daily

During this weird tango of three, there was room for love, but not necessarily prominent. Still it was an improvement on the era of arranged marriages, when a man and a woman could not even meet before tying the knot, or in China's case, unveiling the head scarf of the bride. The result was numerous tragedies.

To understand how social hierarchy figures in traditional Chinese marriages, you need look no further than classic love stories. In The Butterfly Lovers, Liang Shanbo is a poor scholar, while the woman, Zhu Yingtai, is from a rich family. They fall in love, but are torn apart - only to reunite in death and as phantasms of butterflies. In Marriage Between Fairy and Man, a fairy maiden literally falls into the lap of a poor farmer. They start a family, but eventually she has to return to her furious mother.

This theme of poor-boy-meets-rich-girl is repeated so often in Chinese folklore that it is obvious the scenario exemplifies the public's dream rather than reality. People tell these love stories to express their yearning for true love - love that transcends social division. A less mythological version would have the poor boy attaining officialdom before walking down the aisle as the groom - which emphasizes class parity in marriage.

The contemporary variety is called "phoenix man" and "peacock woman". A phoenix man is a male from a poor rural area who goes to college and gets a job in a city. A "peacock woman" is an urbanite who has been brought up in an affluent household. They date and marry. But because of the gap in the backgrounds they often have conflict. Behind the facade of equality, they are still dogged by their parents' social standing.

It is not realistic for a Chinese dating show to have a formula like The Dating Game, the classic show on ABC network, which prohibits questions about the salary and profession of one's potential date. But Chinese producers have pushed the pendulum to the other extreme when they put on guests that scream nouveaux riche. There was one bachelor on a competing show, aired on Zhejiang Satellite Television, who walked on stage and flaunted a document of ownership for a downtown apartment, a key to his Lamborghini and a diamond ring. Diminutive in size, he overshadowed all Arabian oil barons in chutzpah.

Granted, this is good drama. But do we have to stoop so low to get entertained? Do we need to add wannabe models and starlets to every stage? Do we have to turn gold diggers like Ma Nuo into instant celebrities so they can cash in on their relentless pursuit of material wealth?

To me, many of the women are not on the show for a date. They are searching for a venture capitalist that can finance their budding careers in the entertainment industry. Maybe the television producers should tweak their show to match bombshell entrepreneurs with starlet-obsessed financiers. That way, the word love would not make an inappropriate appearance.

If You Are the One shot to notoriety when it highlighted gold diggers like

Ma Nuo. Provided to China Daily

China's first successful dating show is under attack for showcasing materialistic starlets and wannabes rather than true love.

When Jiangsu Satellite Television came out with a hit show early this year my sixth sense told me it would be axed.

If You Are the One is not China's first dating show, but it is the country's first successful one. For each episode, 24 young women stand behind a podium, in control of a light. Half a dozen bachelors are paraded, one for each 10-minute segment. The female contestants turn off the light when they decide to opt out. After several rounds of "showing off his talent", including expositions on love and marriage, the guy gets to choose one of the women who still have their lights on.

The bachelor either walks away with one of the women or, more likely, leaves alone. After which another bachelor is brought in.

What makes the show spicy is the remarks by the female participants when they comment on the bachelor. As there are 24 of them and not everyone is given equal opportunity to pontificate, they have a tendency to make utterances that will not fall to the cutting floor during editing.

One of the women described her marital vision as such: "I'd rather be miserable sitting in a BMW than be happy riding a bicycle." As the bicycle is a mode of transport in China, not a tool of recreation or fitness, what Ma Nuo, a budding model, wants is very clear: wealth over love. She knows money may not bring her happiness, but it is her top priority nonetheless.

This statement quickly became the de facto motto for women like her, and by extension, this dating show, which borrows its title from an earlier hit feature film. For a while, there were so many material girls and gold diggers on China's small screens you'd be forgiven for thinking it was 1920s New York.

Essentially, the show is a victim of its own success. Before the industry watchdogs unleashed their fury, even usually liberal commentators were condemning it as "too boorish". However, defenders had a point when they said the show accurately reflected our social mentality. Say what you like, this is how a lot of Chinese approach dating and mating.

We Chinese, especially women, have always attached great importance to the social status of those we want to marry. Today status is mostly embodied in bank accounts, outsized housing units and luxury vehicles. In the more "idealistic" time when I was a kid, people looked at things like social class - whether one's family was "revolutionary" enough. The very first question asked about a potential date often was: What does his father do?

A 22-year-old might not have much, but if his daddy was a cadre his road ahead was paved with roses. Dating was an elaborate ritual then. Young men and women would turn to a matchmaker, usually a middle-aged woman, for help. She would search her mental database and call up like-minded middle-aged women. When a candidate was identified, she would arrange a meeting for the two. It often took place in a park or at a cinema. The cost involved was not much more than a movie ticket or some snack.

Both sides would report to the "auntie". If one party said "yes" and the other "no", the one who said no would be grilled: "What don't you like about her? I don't see anything wrong? You two look perfect together."

If you turned down two or three dates, you would risk being an outcast. The matchmaker would label you as "too picky" and delete you from her database. And if she happened to be your colleague, you might be bumped from your next promotion.

Chinese are extremely status-conscious when it comes to dating and marriage.

It only happens in fairy tales that a poor boy meets a rich girl and they

get to live happily ever after. Wang Xizeng / For China Daily

During this weird tango of three, there was room for love, but not necessarily prominent. Still it was an improvement on the era of arranged marriages, when a man and a woman could not even meet before tying the knot, or in China's case, unveiling the head scarf of the bride. The result was numerous tragedies.

To understand how social hierarchy figures in traditional Chinese marriages, you need look no further than classic love stories. In The Butterfly Lovers, Liang Shanbo is a poor scholar, while the woman, Zhu Yingtai, is from a rich family. They fall in love, but are torn apart - only to reunite in death and as phantasms of butterflies. In Marriage Between Fairy and Man, a fairy maiden literally falls into the lap of a poor farmer. They start a family, but eventually she has to return to her furious mother.

This theme of poor-boy-meets-rich-girl is repeated so often in Chinese folklore that it is obvious the scenario exemplifies the public's dream rather than reality. People tell these love stories to express their yearning for true love - love that transcends social division. A less mythological version would have the poor boy attaining officialdom before walking down the aisle as the groom - which emphasizes class parity in marriage.

The contemporary variety is called "phoenix man" and "peacock woman". A phoenix man is a male from a poor rural area who goes to college and gets a job in a city. A "peacock woman" is an urbanite who has been brought up in an affluent household. They date and marry. But because of the gap in the backgrounds they often have conflict. Behind the facade of equality, they are still dogged by their parents' social standing.

It is not realistic for a Chinese dating show to have a formula like The Dating Game, the classic show on ABC network, which prohibits questions about the salary and profession of one's potential date. But Chinese producers have pushed the pendulum to the other extreme when they put on guests that scream nouveaux riche. There was one bachelor on a competing show, aired on Zhejiang Satellite Television, who walked on stage and flaunted a document of ownership for a downtown apartment, a key to his Lamborghini and a diamond ring. Diminutive in size, he overshadowed all Arabian oil barons in chutzpah.

Granted, this is good drama. But do we have to stoop so low to get entertained? Do we need to add wannabe models and starlets to every stage? Do we have to turn gold diggers like Ma Nuo into instant celebrities so they can cash in on their relentless pursuit of material wealth?

To me, many of the women are not on the show for a date. They are searching for a venture capitalist that can finance their budding careers in the entertainment industry. Maybe the television producers should tweak their show to match bombshell entrepreneurs with starlet-obsessed financiers. That way, the word love would not make an inappropriate appearance.