雅思阅读:Now you know

雅思阅读:Now you know

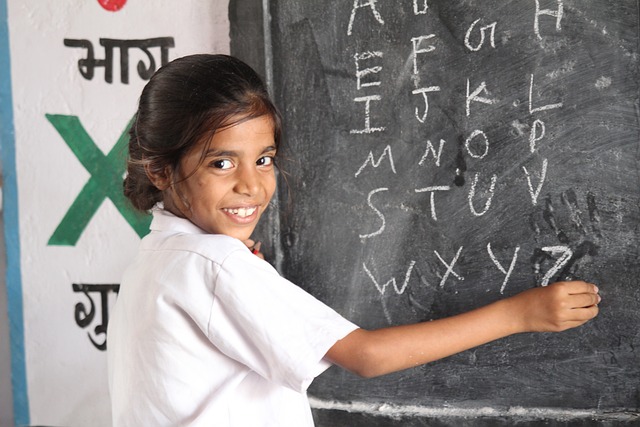

When should you teach children, and when should you let them explore?

IT IS one of the oldest debates in education. Should teachers tell pupils the way things are or encourage them to find out for themselves? Telling children truths about the world helps them learn those facts more quickly. Yet the efficient learning of specific facts may lead to the assumption that when the adult has finished teaching, there is nothing further to learnbecause if there were, the adult would have said so. A study just published in Cognition by Elizabeth Bonawitz of the University of California, Berkeley, and Patrick Shafto of the University of Louisville, in Kentucky, suggests that is true.

Dr Bonawitz and Dr Shafto arranged for 85 four- and five-year-olds to be presented, during a visit to a museum, with a novel toy that looked like a tangle of coloured pipes and was capable of doing many different things. They wanted to know whether the way the children played with the toy depended on how they were instructed by the adult who gave it to them.

One group of children had a strictly pedagogical introduction. The experimenter said Look at my toy! This is my toy. Im going to show you how my toy works. She then pulled a yellow tube out of a purple tube, creating a squeaking sound. Following this, she said, Wow, see that? This is how my toy works! and then demonstrated the effect again.

With a second group of children, the experimenter acted differently. She interrupted herself after demonstrating the squeak by saying she had to go and write something down, thus suggesting that she might not have finished the demonstration. With a third group, she activated the squeak as if by accident. To a fourth, the toy was simply presented with the comment, Wow, see this toy? Look at this!

After these varied introductions, the children were left with the toy and allowed to play. They might discover that, as well as the squeaker, the toy had a button inside one tube which activated a light, a keypad that played musical notes, and an inverting mirror inside one of the tubes. All the children were told to let the experimenter know when they had finished playing and were asked by the instructor if they were done if they stopped playing for more than five consecutive seconds. The entire interaction was recorded on video.

Footage of each child playing was passed to a research assistant who was ignorant of the purpose of the study. The assistant was asked to record the total playing time, the number of different actions the child performed, the time spent playing with the squeak, and the number of other functions the child discovered.

The upshot was that children in the first group spent less time playing than those in the second , the third or the fourth . Those in the first group also tried out four different actions, on average. The others tried 5.3, 5.9 and 6.2, respectively. A similar pattern pertained to the number of functions other than the squeak that the children found.

The researchers conclusion was that, in the context of strange toys of unknown function, prior explanation does, indeed, inhibit exploration and discovery. Generalising from that would be ambitious. But it suggests that further research might be quite a good idea.

雅思阅读:Now you know

When should you teach children, and when should you let them explore?

IT IS one of the oldest debates in education. Should teachers tell pupils the way things are or encourage them to find out for themselves? Telling children truths about the world helps them learn those facts more quickly. Yet the efficient learning of specific facts may lead to the assumption that when the adult has finished teaching, there is nothing further to learnbecause if there were, the adult would have said so. A study just published in Cognition by Elizabeth Bonawitz of the University of California, Berkeley, and Patrick Shafto of the University of Louisville, in Kentucky, suggests that is true.

Dr Bonawitz and Dr Shafto arranged for 85 four- and five-year-olds to be presented, during a visit to a museum, with a novel toy that looked like a tangle of coloured pipes and was capable of doing many different things. They wanted to know whether the way the children played with the toy depended on how they were instructed by the adult who gave it to them.

One group of children had a strictly pedagogical introduction. The experimenter said Look at my toy! This is my toy. Im going to show you how my toy works. She then pulled a yellow tube out of a purple tube, creating a squeaking sound. Following this, she said, Wow, see that? This is how my toy works! and then demonstrated the effect again.

With a second group of children, the experimenter acted differently. She interrupted herself after demonstrating the squeak by saying she had to go and write something down, thus suggesting that she might not have finished the demonstration. With a third group, she activated the squeak as if by accident. To a fourth, the toy was simply presented with the comment, Wow, see this toy? Look at this!

After these varied introductions, the children were left with the toy and allowed to play. They might discover that, as well as the squeaker, the toy had a button inside one tube which activated a light, a keypad that played musical notes, and an inverting mirror inside one of the tubes. All the children were told to let the experimenter know when they had finished playing and were asked by the instructor if they were done if they stopped playing for more than five consecutive seconds. The entire interaction was recorded on video.

Footage of each child playing was passed to a research assistant who was ignorant of the purpose of the study. The assistant was asked to record the total playing time, the number of different actions the child performed, the time spent playing with the squeak, and the number of other functions the child discovered.

The upshot was that children in the first group spent less time playing than those in the second , the third or the fourth . Those in the first group also tried out four different actions, on average. The others tried 5.3, 5.9 and 6.2, respectively. A similar pattern pertained to the number of functions other than the squeak that the children found.

The researchers conclusion was that, in the context of strange toys of unknown function, prior explanation does, indeed, inhibit exploration and discovery. Generalising from that would be ambitious. But it suggests that further research might be quite a good idea.