Good or well?

Shirlie writes:

I like your explanation in your column titled "Safe or Safety". I think your idea is clear and easy to understand. I agree with you on the "bizarre" things, which often happen to me when I teach.

I am an English teacher at a middle school. I try my hard to avoid the "bizarre" things but just find it unavoidable. It happens everywhere, in the text book, in everyday test paper, and I often get confused by some multiple-choice questions. For example, one question is like this: You don't look ____. You'd better go to see a doctor. A wonderfully B well C nice D good.

The preferred answer is B (well). So, how can I explain to my students they should choose B but not D?

In my experience, when someone really doesn't feel good, the native speaker likes to say: Are you ok? or Are you alright? or Do you feel good? or in some other ways. Thank you very much for your help.

My comments:

When people say you look good, they mean you look pretty and smart - they are not talking about your physical wellbeing, or the lacks thereof. When they say you don't look well, they mean you look ill (and you'd better go and see a doctor).

If you ask the native speaker why this is so, they'll probably say that it's just the way it is, that they've grown up saying so without having given it much thought one way or the other.

Grammar, you see, is a series of agreements (over how to string words together) put in place to avoid misunderstanding. It's developed through experiment, over time and by trial and error. But grammar rules are not as strict as, say traffic regulations and criminal laws. That's why, if someone misspeaks, no-one will call the police. Language usages are more of a habitual and customary nature (as they are to the native speaker) than one about logic and reason. That's why grammar of one language often appears illogical and irreconcilable to foreigners, who've been used only to the equally peculiar and idiosyncratic tongue of their own.

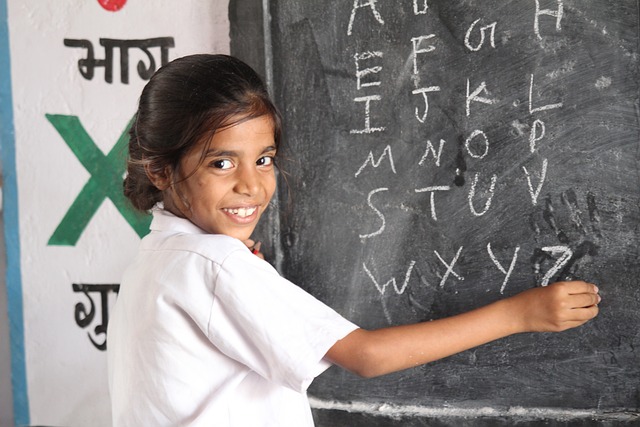

In the process of learning a language, people put little store by grammar rules, especially in the beginning. Children, you see, learn to speak by imitating parents, fellow pupils and others rather than by memorizing grammatical rules and regulations. To my knowledge, no children, however prodigious, have learned a language, native or foreign, by doing multiple-choice tests alone, which seems to be a prevalent practice in Chinese schools.

The fact that English for the Chinese is a foreign language is often taken as a good excuse for failure, but it's a poor excuse. All excuses are in fact bad excuses. Good excuses are even worse. A foreign language is still a language, isn't it?

This foreign language thing is overblown and exaggerated in China. There's too much fear of it in here, it seems. People are not taking it easy, one step a time. Children are not given enough opportunities to speak and be familiar with the language before they are being tested about it.

If you recall our modern history, you'll perhaps realize that it took some time for us to come to terms with foreigners as different groups. In the beginning, all Westerners, whether they are German, English, French or Russian, are called foreign devils because at the first glances they looked the same to the Chinese eye. They were all red-faced, blue-eyed and with a big nose and were generally up to no good (considering what they were here for in the very beginning).

The Big Noses didn't quite look human (the way one of us looked human). Only when we got to know them well (not good) enough do they begin to appear human, each with their individual nationalities, personalities and so forth. But in the beginning, before we got to understand the finer details about each and everyone of them, they all looked odd and the same - it just didn't make sense.

It's the same way with English as a foreign language. It is only when one gets fairly acquainted with the nitty-gritty do they begin to find it reasonable (in its own way) and, in fact, interesting.

I can't tell you, Shirlie, how you may explain to your student why when people don't look WELL they need to see a doctor, but if I were you, I'd encourage them to keep listening (to native speakers preferably, via videos and tapes in case a real Big Nose is hard to come by) and to keep speaking. If mistakes are made, so what, just do it again.

I can imagine that somewhere along the line you'll tell them "never mind reasons, it's the way it is" or, as any mother will say to a child, "you'll understand when you grow up." You may sound a bit mystical that way but I think you can get away with it to some extent.

So long as you keep encouraging them to listen and to speak and see to it that they do. That way, eventually, they'll all look good.

And they'll make you, Shirlie, look good too.

Shirlie writes:

I like your explanation in your column titled "Safe or Safety". I think your idea is clear and easy to understand. I agree with you on the "bizarre" things, which often happen to me when I teach.

I am an English teacher at a middle school. I try my hard to avoid the "bizarre" things but just find it unavoidable. It happens everywhere, in the text book, in everyday test paper, and I often get confused by some multiple-choice questions. For example, one question is like this: You don't look ____. You'd better go to see a doctor. A wonderfully B well C nice D good.

The preferred answer is B (well). So, how can I explain to my students they should choose B but not D?

In my experience, when someone really doesn't feel good, the native speaker likes to say: Are you ok? or Are you alright? or Do you feel good? or in some other ways. Thank you very much for your help.

My comments:

When people say you look good, they mean you look pretty and smart - they are not talking about your physical wellbeing, or the lacks thereof. When they say you don't look well, they mean you look ill (and you'd better go and see a doctor).

If you ask the native speaker why this is so, they'll probably say that it's just the way it is, that they've grown up saying so without having given it much thought one way or the other.

Grammar, you see, is a series of agreements (over how to string words together) put in place to avoid misunderstanding. It's developed through experiment, over time and by trial and error. But grammar rules are not as strict as, say traffic regulations and criminal laws. That's why, if someone misspeaks, no-one will call the police. Language usages are more of a habitual and customary nature (as they are to the native speaker) than one about logic and reason. That's why grammar of one language often appears illogical and irreconcilable to foreigners, who've been used only to the equally peculiar and idiosyncratic tongue of their own.

In the process of learning a language, people put little store by grammar rules, especially in the beginning. Children, you see, learn to speak by imitating parents, fellow pupils and others rather than by memorizing grammatical rules and regulations. To my knowledge, no children, however prodigious, have learned a language, native or foreign, by doing multiple-choice tests alone, which seems to be a prevalent practice in Chinese schools.

The fact that English for the Chinese is a foreign language is often taken as a good excuse for failure, but it's a poor excuse. All excuses are in fact bad excuses. Good excuses are even worse. A foreign language is still a language, isn't it?

This foreign language thing is overblown and exaggerated in China. There's too much fear of it in here, it seems. People are not taking it easy, one step a time. Children are not given enough opportunities to speak and be familiar with the language before they are being tested about it.

If you recall our modern history, you'll perhaps realize that it took some time for us to come to terms with foreigners as different groups. In the beginning, all Westerners, whether they are German, English, French or Russian, are called foreign devils because at the first glances they looked the same to the Chinese eye. They were all red-faced, blue-eyed and with a big nose and were generally up to no good (considering what they were here for in the very beginning).

The Big Noses didn't quite look human (the way one of us looked human). Only when we got to know them well (not good) enough do they begin to appear human, each with their individual nationalities, personalities and so forth. But in the beginning, before we got to understand the finer details about each and everyone of them, they all looked odd and the same - it just didn't make sense.

It's the same way with English as a foreign language. It is only when one gets fairly acquainted with the nitty-gritty do they begin to find it reasonable (in its own way) and, in fact, interesting.

I can't tell you, Shirlie, how you may explain to your student why when people don't look WELL they need to see a doctor, but if I were you, I'd encourage them to keep listening (to native speakers preferably, via videos and tapes in case a real Big Nose is hard to come by) and to keep speaking. If mistakes are made, so what, just do it again.

I can imagine that somewhere along the line you'll tell them "never mind reasons, it's the way it is" or, as any mother will say to a child, "you'll understand when you grow up." You may sound a bit mystical that way but I think you can get away with it to some extent.

So long as you keep encouraging them to listen and to speak and see to it that they do. That way, eventually, they'll all look good.

And they'll make you, Shirlie, look good too.