悼念:波兰女诗人维斯瓦娃·辛波丝卡

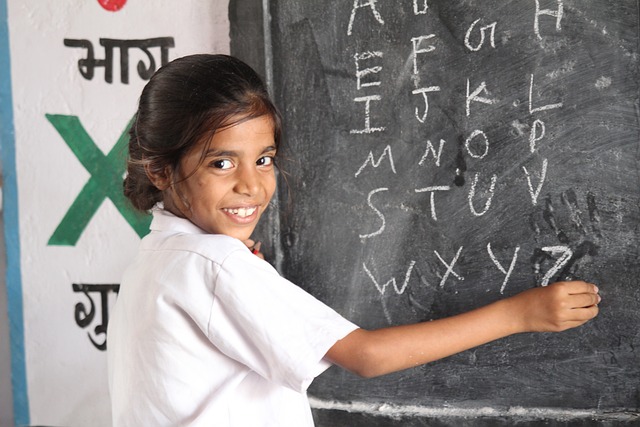

Obituary:辛波丝卡,生于波兰的小镇布宁的一个知识分子家庭里。当时,她的国家刚刚摆脱第一次世界大战的阴影。一九三一年全家迁往波兰南部的克拉科夫。在辛波丝卡的每一本诗集中,几乎都可以看到她追求新风格、尝试新技法的用心。 她擅长自日常生活汲取喜悦,以小隐喻开发深刻的思想,寓严肃于幽默、机智,是以 小搏大,举重若轻的语言大师。于1996年获得诺贝尔文学奖。2001年成为美国文学艺术学院名誉会员,这是美国授予杰出艺术家的最重要荣誉。2024年2月1日,在克拉科夫逝世,享年88岁。

Wislawa Szymborska

维斯瓦娃辛波丝卡

Wislawa Szymborska, poet, died on February 1st, aged 88.

诗人维斯瓦娃辛波丝卡于2月1日辞世,终年88岁。

WHEN Wislawa Szymborska won the worlds top literary prize in 1996, her friends called it the Nobel disaster. This was not just because she had spent an uncomfortable night before the award ceremony in the bath: the bathroom was the only part of her quarters in a grand Stockholm hotel in which she could manage to turn on the light. Nor was it the torture she felt in having to make a speech one of only three she had given in her life. The real disaster was the trauma of fame and fortune. It was years before she could publish another poem. Her fans delight in her Nobel prize was mixed with disappointment that it had rendered her mute.

1966年,维斯瓦娃辛波丝卡荣膺文学最高荣誉,朋友却打诨为诺贝尔灾难。在颁奖的前一天,她还在浴室里挨过了一个难受的夜晚,因为在豪华的斯德哥尔摩酒店,浴室是其房间里唯一一处能找到灯光的地方。辛波丝卡一生中只做过三次演讲,每一次都身心折磨,这次也不例外。当然,真正的灾难要数名誉与财富带来的创伤,折桂诺贝尔奖后,粉丝高兴之余夹杂着些许失望,因为奖项也使这位桂冠诗人哑言,许多几年后才发表了一首诗。

Like many Poles who survived the war, Ms Szymborska readily accepted communism in early life, seeing it as a salvation for a ruined world. Early poems praised Lenin and young communists building a steel works. Later she blamed her own foolishness, naivety and perhaps intellectual laziness, but some found it hard to forgive her for signing a petition in 1953 backing a show trial of four priests.

和许多战后余生的波兰人一样,辛波丝卡早年欣然接受共产主义洗礼,视之为对世界千疮百孔下的救赎。赞扬列宁,歌颂年轻的共产党建钢厂等题材常见于早期的诗中。随后,她自我嘲讽道愚蠢,天真,还有一点思维惰性。1953年,为支持4位神父的审判秀辛波丝卡在请愿书签字,许多人都无法接受她这一做法。

Her ironic and individualistic spirit was ill fitted to the grey conformity of peoples Poland: the Nobel citation said she wrote with the ease of Mozart and the fury of Beethoven. Playful, subtle and haunting, her poetry could never be in harmony with the socialist realist style dictated by the countrys cultural commissars. She mocked their intolerance of dissent in a poem on pornography:

辛波丝卡性情自讽而独特,难以融入波兰人民共和国那乏味的一致:诺贝尔奖褒奖她文如莫扎特一样舒缓,贝多芬一样愤怒。她的诗诙谐而精致,让人回味无穷,却与国家文化政委规定下的社会主义现实风格格不入。她以色情为题,借一首小诗嘲讽了这个狭隘的国度。

Theres nothing more debauched than thinking.

This sort of wantonness runs wild like a wind-borne weed on a plot laid out for daisies.

思想竟是如此堕落。

放纵滋蔓,犹如风媒后的野草,静候雏菊临幸。

Communism she likened to the abominable snowman horrid and she stayed in the party until 1966, hoping to try to ix it all from the inside. That, she said later, had been another delusion.

辛波丝卡将共产主义比作可憎的雪人,恐怖而虚幻。1966年还是党员的她希望从党内部一一收拾掉。随后她自嘲道这不过幻想一场罢。

Ms Szymborska was 16 when Hitler and Stalin carved up Poland between them. Old age was the privilege of rocks and trees, she wrote. Although not a mainstream dissident, her poems distilled the essence of individual stubbornness in the face of what the party bosses said was historical inevitability.

16岁那年小辛波丝卡经历希特勒与斯大林瓜分祖国。年迈是岩石与树木的特权她于是写道。尽管异议称不上主流,面对党派大佬鼓吹历史必然时,诗中却将那份骨子中的倔强娓娓道来。

I believe in the refusal to take part.

I believe in the ruined career.

I believe in the wasted years of work.

I believe in the secret taken to the grave.

These words soar for me beyond all rules without seeking support from actual examples.

My faith is strong, blind, and without foundation.

不去参与,

因已江郎才尽。

虚度光阴,

真理却永存于地下。

文字激荡,

跨越一切樊篱,不为现实所缚

我无依靠的灵魂啊,

竟是如此坚强,如此迷茫。

Obituary:辛波丝卡,生于波兰的小镇布宁的一个知识分子家庭里。当时,她的国家刚刚摆脱第一次世界大战的阴影。一九三一年全家迁往波兰南部的克拉科夫。在辛波丝卡的每一本诗集中,几乎都可以看到她追求新风格、尝试新技法的用心。 她擅长自日常生活汲取喜悦,以小隐喻开发深刻的思想,寓严肃于幽默、机智,是以 小搏大,举重若轻的语言大师。于1996年获得诺贝尔文学奖。2001年成为美国文学艺术学院名誉会员,这是美国授予杰出艺术家的最重要荣誉。2024年2月1日,在克拉科夫逝世,享年88岁。

Wislawa Szymborska

维斯瓦娃辛波丝卡

Wislawa Szymborska, poet, died on February 1st, aged 88.

诗人维斯瓦娃辛波丝卡于2月1日辞世,终年88岁。

WHEN Wislawa Szymborska won the worlds top literary prize in 1996, her friends called it the Nobel disaster. This was not just because she had spent an uncomfortable night before the award ceremony in the bath: the bathroom was the only part of her quarters in a grand Stockholm hotel in which she could manage to turn on the light. Nor was it the torture she felt in having to make a speech one of only three she had given in her life. The real disaster was the trauma of fame and fortune. It was years before she could publish another poem. Her fans delight in her Nobel prize was mixed with disappointment that it had rendered her mute.

1966年,维斯瓦娃辛波丝卡荣膺文学最高荣誉,朋友却打诨为诺贝尔灾难。在颁奖的前一天,她还在浴室里挨过了一个难受的夜晚,因为在豪华的斯德哥尔摩酒店,浴室是其房间里唯一一处能找到灯光的地方。辛波丝卡一生中只做过三次演讲,每一次都身心折磨,这次也不例外。当然,真正的灾难要数名誉与财富带来的创伤,折桂诺贝尔奖后,粉丝高兴之余夹杂着些许失望,因为奖项也使这位桂冠诗人哑言,许多几年后才发表了一首诗。

Like many Poles who survived the war, Ms Szymborska readily accepted communism in early life, seeing it as a salvation for a ruined world. Early poems praised Lenin and young communists building a steel works. Later she blamed her own foolishness, naivety and perhaps intellectual laziness, but some found it hard to forgive her for signing a petition in 1953 backing a show trial of four priests.

和许多战后余生的波兰人一样,辛波丝卡早年欣然接受共产主义洗礼,视之为对世界千疮百孔下的救赎。赞扬列宁,歌颂年轻的共产党建钢厂等题材常见于早期的诗中。随后,她自我嘲讽道愚蠢,天真,还有一点思维惰性。1953年,为支持4位神父的审判秀辛波丝卡在请愿书签字,许多人都无法接受她这一做法。

Her ironic and individualistic spirit was ill fitted to the grey conformity of peoples Poland: the Nobel citation said she wrote with the ease of Mozart and the fury of Beethoven. Playful, subtle and haunting, her poetry could never be in harmony with the socialist realist style dictated by the countrys cultural commissars. She mocked their intolerance of dissent in a poem on pornography:

辛波丝卡性情自讽而独特,难以融入波兰人民共和国那乏味的一致:诺贝尔奖褒奖她文如莫扎特一样舒缓,贝多芬一样愤怒。她的诗诙谐而精致,让人回味无穷,却与国家文化政委规定下的社会主义现实风格格不入。她以色情为题,借一首小诗嘲讽了这个狭隘的国度。

Theres nothing more debauched than thinking.

This sort of wantonness runs wild like a wind-borne weed on a plot laid out for daisies.

思想竟是如此堕落。

放纵滋蔓,犹如风媒后的野草,静候雏菊临幸。

Communism she likened to the abominable snowman horrid and she stayed in the party until 1966, hoping to try to ix it all from the inside. That, she said later, had been another delusion.

辛波丝卡将共产主义比作可憎的雪人,恐怖而虚幻。1966年还是党员的她希望从党内部一一收拾掉。随后她自嘲道这不过幻想一场罢。

Ms Szymborska was 16 when Hitler and Stalin carved up Poland between them. Old age was the privilege of rocks and trees, she wrote. Although not a mainstream dissident, her poems distilled the essence of individual stubbornness in the face of what the party bosses said was historical inevitability.

16岁那年小辛波丝卡经历希特勒与斯大林瓜分祖国。年迈是岩石与树木的特权她于是写道。尽管异议称不上主流,面对党派大佬鼓吹历史必然时,诗中却将那份骨子中的倔强娓娓道来。

I believe in the refusal to take part.

I believe in the ruined career.

I believe in the wasted years of work.

I believe in the secret taken to the grave.

These words soar for me beyond all rules without seeking support from actual examples.

My faith is strong, blind, and without foundation.

不去参与,

因已江郎才尽。

虚度光阴,

真理却永存于地下。

文字激荡,

跨越一切樊篱,不为现实所缚

我无依靠的灵魂啊,

竟是如此坚强,如此迷茫。